Muybridge first photographed the human figure in motion on March 4th 1879. However, he did not focus on the human body until his contract at Pennsylvania University began in May 1884, resulting in two volumes of work dedicated to photographs of human subjects.

This extensive work depicted men, women and children variously running, jumping, falling and carrying out athletic or mundane activities. This section of Muybridge's work reiterates the imperative Muybridge felt to explore time in modernity, as explored here through 'Animals in Motion'. However, it also depicts, and perhaps helps consolidate a specifically American set of contemporary aspirations and ideals surrounding identity at Pennsylvania University.

As discussed in 'Foreign Bodies', the 19th Century in North America embodied strict racial hierarchies which helped unite the 'civilized' democratic world as a team, whilst validating the occupation of Native American Land. But this hierarchy was not only produced through the negative representation of non-western people. Racial ideals were configured for a new generation of western individuals too. And just as photography helped define non-western stereotypes it helped inscribe a new set of aspirations for westerners.

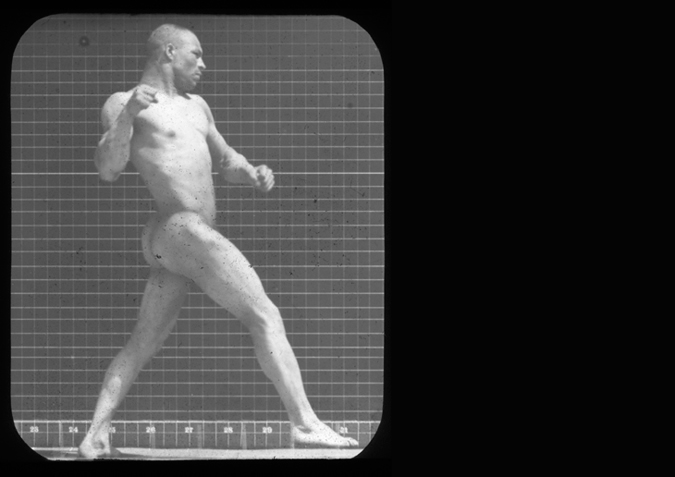

In his motion photography, Muybridge only used one non-white model - Ben Bailey - a mixed race male. Interestingly, Muybridge never used an anthropometric grid behind his subjects until he photographed Bailey, and never photographed the human figure without one afterwards (Brown, 2005 p637).

As Brown states, anthropometric grids were commonly used in 19th Century ethnographic photography to make objective studies of non-western bodies: highlighting physical differences which had grown to signify a lack of civilization to the western eye. Grids were particularly useful in this way as they gave photographic work the 'aesthetic of science - dispassionate, orderly, coherent' (Solnit, 2003, p195) which helped boost the truth-value of the photograph, and therefore helped inscribe racial stereotypes.

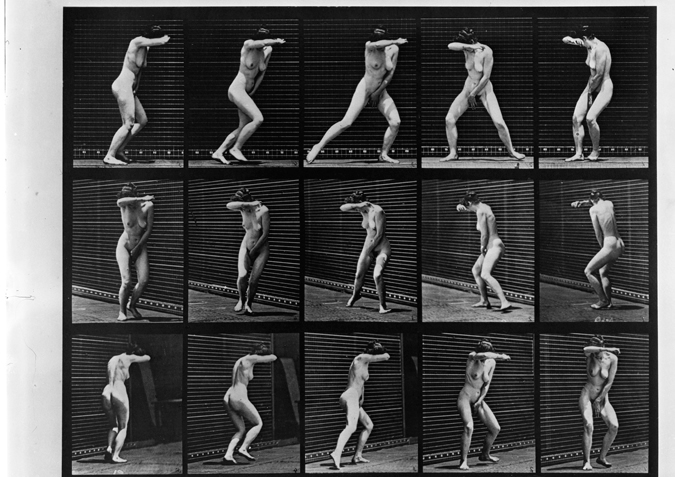

Gridded photographs of Ben Bailey helped situate him as 'a racialised object', reinforcing common negative stereotypes of the time surrounding primitivism and hyper-virility through his particularly muscular frame (Brown, p638). Conversely, Muybridge’s photographs of white males helped define a new positive set of ideals surrounding masculinity. These males were athletic, but not so overtly muscular, and represented a wider societal desire for young white males to achieve both intellectual and physical excellence; itself a subversion of stereotypes born from the previous generation of American intellectuals, who had suffered widely from neurasthenia.

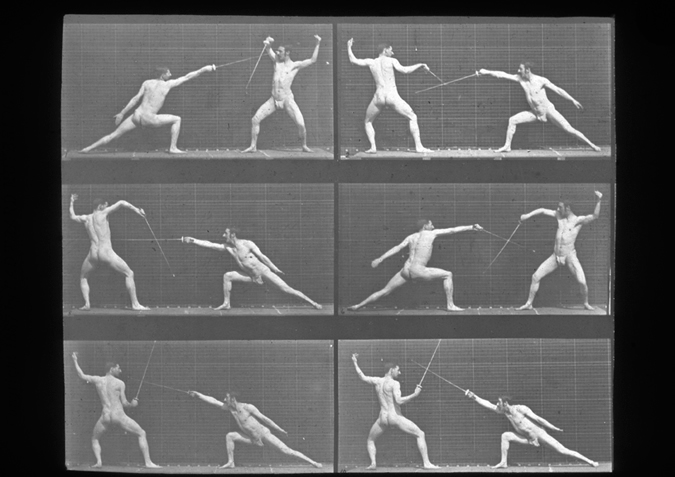

Bailey thus provided a frighteningly exaggerated version of the physical ideal, whereas Muybridge's white male subjects - mostly students and athletes from Pennsylvania University - represented a balanced version of this new aspiration for the next generation of American intellectual leaders. Pictures of men engaged in sporting events including fencing and boxing, as well as other physical activities such as hammering and lathing helped reinforce the dimensions of this new ideal masculinity - competitive, athletic and physically as well as intellectually able.

Just as ideals of maleness were embodied by Muybridge's photography, so were images of femininity. These were more traditionally entrenched, but persuasive nonetheless. Women were pictured in graceful, domestic or maternal stances - and as is often the case in artistic representation, displayed for the viewer in representations far more sexualized than any pragmatic male nudity: often erring towards fantasy (Cresswell, 2006, p65)

Therefore white male athletic bodies and female sexualized domestic bodies represented racial stereotypes and social hierarchies just as clearly as images of Ben Bailey. Indeed, these were ideals consolidated by a final set of human bodies represented by Muybridge’s motion studies, those of disabled people - represented in a particularly scientistic and objective manner.

The plain contrast between medical abnormality and the physical ideal represented by this work clearly illustrates the 19th century trend of racial and bodily hierarchy Muybridge's work functioned within. We might find this horrifying now, but we must not blame Muybridge for his sensibilities. A man of his time, Muybridge is an essential orator for the world he inhabited.

Select Bibliography

Brown, Elspeth H. 'Racialising the Virile Body: Eadweard Muybridge's Locomotion Studies 1883-1887. In Gender and History Vol 17 no 3 Nov 2005 pp627-656.

Cresswell ,Tim 'Capturing mobility: mobility and meaning in the photography of Eadweard Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey' On the Move (New York Routledge 2006)

Foucault, Michel Society Must Be Defended (London, Penguin, 2003)

Hargreaves, Roger The Beautiful and the Damned: the Creation of Identity in Nineteenth Century Photography (Hampshire, Lund Humphries 2001)

Poole, Deborah Vision, Race and Modernity (New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1997)

Solnit, Rebecca Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge. (London: Bloomsbury, 2003)

Introducing Muybridge

Introducing Muybridge Landscape

Landscape The Modern City

The Modern City Transport and Trade

Transport and Trade Foreign Bodies

Foreign Bodies Animal in Motion

Animal in Motion Human Figure in Motion

Human Figure in Motion Zoöpraxography

Zoöpraxography